The appeal of the game

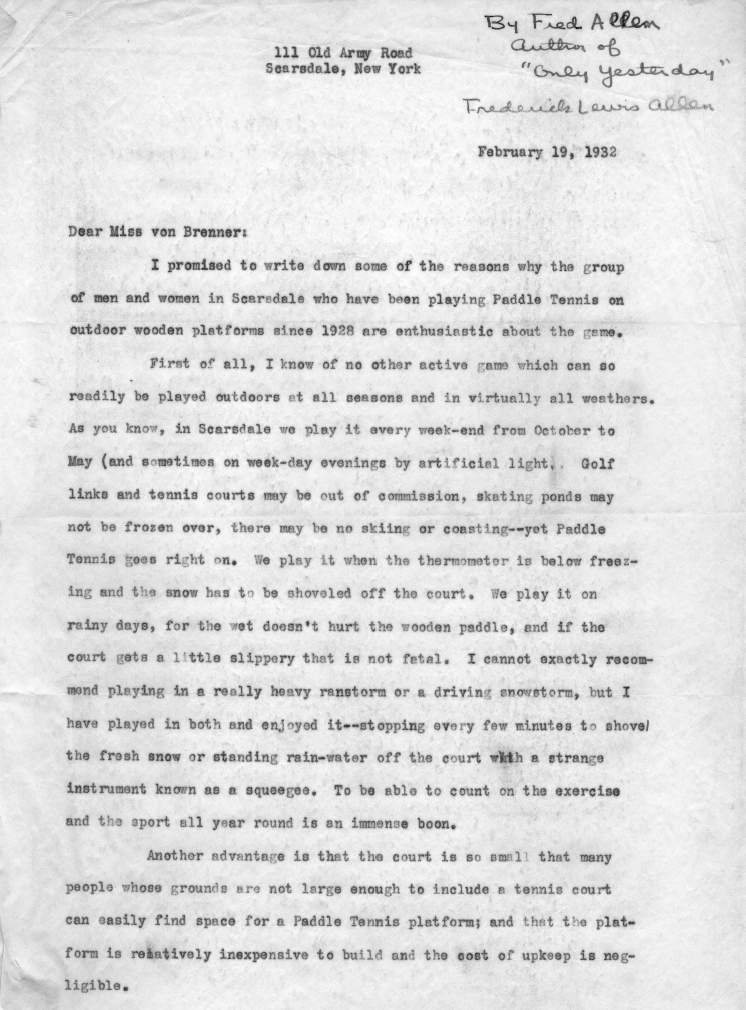

Frederick Lewis Allen, Editor of Harper’s Magazine, wrote the following letter on February 19, 1932 to a lady who had asked him what he thought of the game. The letter was written before the Evans invention had made taking balls off the backstop an assured success, before the sanding technique had practically eliminated slipping during a rain, and when the game was still largely confined to those who learned it on the Cogswell court.

“I know of no other active game which can so readily be played outdoors at all seasons and in virtually all weathers. In Scarsdale we play it every week-end from October to May (and sometimes on week-day evenings by artificial light). Golf links and tennis courts may be out of commission; skating ponds may not be frozen over; there may be no skiing or coasting—yet Paddle Tennis goes right on. We play it when the thermometer is below freezing and the snow has to be shoveled off the court. We play it on rainy days, for the wet doesn’t hurt the wooden paddles, and if the court gets a little slippery that is not fatal. I cannot exactly recommend playing in a really heavy rainstorm or a driving snow storm’, but I have played in both and enjoyed it—stopping every few minutes to shovel the fresh snow or standing rainwater off the court with a strange instrument known as a squeegee. To be able to count on the exercise and the sport all year round is an immense boon.

Another advantage is that the court is so small that many people whose grounds are not large enough to include a tennis court can easily find space for a Paddle Tennis platform; and that the platform is relatively inexpensive to build and the cost of upkeep is negligible. But these advantages would count for little if the game itself were inferior. I consider it one of the best games ever invented

Anybody who has ever played lawn tennis finds it absurdly easy to learn: I have seen men take a respectable part in a doubles match with seasoned players after only an hour’s practice. It is one of those games in which the relatively poor player is not completely outclassed and humiliated; even the duffer can return enough drives to feel that he is something more than a helpless bystander. One reason is that the paddle is so short that the ball is easy to hit quickly and with fair accuracy. You can pick any four players out of a group and be sure that they will be able to work up a pretty good match.

Yet I must not give the impression that because the game is easy to learn it is mild and innocuous. Although Paddle Tennis is less tiring than lawn tennis because the court being smaller there is less running, on the other hand the ball goes back and forth much more quickly than in lawn tennis; the rallies are usually longer, the pauses between them are shorter, and the players are on the move every second. They can (and do) hit the ball just as hard as they please; and there are plenty of opportunities for strategic placing, for outguessing one’s opponent, for alternating smashes with lobs or deep drives with cross-court pokes at the net. Most of the play, by the way, is near the net—in doubles, at least—and that means quick and exciting action. If anybody thinks Paddle Tennis is merely a children’s game or a sort of overgrown ping-pong, the sight of a fast set of men’s doubles will soon remove the idea from his mind.

If the fun that thirty or forty of us have had in Scarsdale is any criterion, it offers first-class sport—to say nothing of exercise—to anybody who can hit a sponge-rubber ball with a wooden paddle and move faster than a walk.”

Source: Adapted from Fessenden S. Blanchard, Paddle Tennis, 1944