The future of the court – more innovation

Court construction has come along way from that first deck built in 1928. New technology is being put to work to make them better all the time. PTM had the update.

Ideas, Aspirations and Actualities

Have you been on a court that seemed different recently? Did you just notice that some courts have different colors? Courts have been changing bit by bit over time, but major changes could be in the future. What does the court of the future look like?

What if it didn’t have snowboards? Even in the snowy Northeast or the frigid Midwest? What if the courts weren’t aluminum? What if the surface didn’t have grit since it never got slippery from the snow? Can’t you hear the knees and backs out there applauding? All the other elements of the court—lights, door locks, wires, net posts—could be or have been reconceived as well.

There are innovators out there thinking aboUt the court materials for our growing sport, and striving to make changes where needed, taking into consideration cost and viability. What if?

Surfaces

The standard surface of the platform tennis court is aluminum. It’s durable, it can be resurfaced without compromising the integrity of the material, and it can endure temperature changes from Mother Nature and man-made heaters. It has withstood the test of time. Many of the first aluminum courts, built in the 1980s, show little sign of wear. So does it need to be changed?

When platform tennis migrated south, heaters were not a necessity and the courts didn’t have to be raised. Concrete was the first accepted alternative surface. As Bob Stratton, a player living in Atlanta, put it, “While I appreciate the ‘legacy of the game,’ we were able to move from wooden to aluminum courts. Why not other surfaces?”

Stratton, who is not a court builder, but a materials engineer and business owner, is interested in progress. When he travels to trade shows, he investigates different courtsurfaces and talks about them with different vendors. “There is an international sport out there that has championships played on four different surfaces. Why not ours?”

He has explored materials used on oil rigs, which has built-in grit and is non-conductive, important for outside work and play. The pultruded composite fiberglass decking is half the cost of similar aluminum. “You can customize the design to make it as flexible or stiff as you want. The grit level can also be customized,” Stratton explained. He also looked at the aircraft carrier surface. Sized in 2×2 tiles, it is made of a vacuum-formed plastic. Aircraft carriers use deicer when they need to get rid of snow and ice, and in Atlanta, bar the recent unusual spate of winter storms, they don’t need to de-ice too often. It is a surface that would work with radiant heat, another innovation being looked into for platform tennis courts.

Stratton’s contribution to the research and intelligence gathering extends to all facets of the court, but he’s just experimenting. He sees the possibilities outside of the standards. “Even the screen posts could be made of a different material. I think there is a whole lot that could be done on materials to lower costs. We need resources, grants, and to realize the possibilities,” Stratton opined. “If someone could purchase large volumes of the materials to get the cost down, and have the builders buy from that source, the courts would be standarized and the cost could be lower. Court cost, I believe, is an impediment to the growth of this sport.”

Jean Kempner, a teaching pro and player for over 30 years, who now lives in Las Vegas, has ideas about courts for the North. He, too, isn’t convinced that courts need to be raised anymore. “We don’t need heat on the courts– at least players don’t in order to stay warm; we need snow and ice melting capability. The propane heaters in place these days always have hot spots and cold spots and don’t offer thorough drying.”

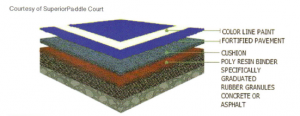

Kempner is trying to convince people that building platform tennis courts with a cushioned tennis court surface, such as the US Open and Australian Open’s Plexicushion, is a good solution. “This helps reduce the hurt backs and bad knees that result from playing lots of paddle on unforgiving grit-coated courts,” Kempner stated, one of the main reasons he thinks new surfaces need to be explored. There would be no need for grit, which some believe causes injury. Kempner has created a whole concept court, which is patent pending, complete with removable net posts, so that the court can be used for other sports during downtime. [Look for Kempner's Superior Court° system online.]

All of the “surfaces of the future” need about the same maintenance as today’s aluminum courts—resurfacing every three to five years—and cost about the same or less. Aluminum courts are tried and true because they last in the harsh elements of the North and Midwest for decades before they need replacing. “The aluminum courts we built in the early 1980s still look and play great,” said David Dodge of Total Platform Tennis.

Radiant Heat

The new surfaces described above would only work with a radiant heating system. There may be a radiant heat system that works on raised courts, also. While the expense of putting them in is high, they are more cost efficient over time.

Court builder Chris Casiraghi, of Reilly Green Mountain, talked about some heating systems they’ve tried. “Electric is the easiest to install for most clubs, but it is cost prohibitive to operate because of the high cost of electricity. It costs about $40,000 to install, but it keeps up with one inch of snow per hour. The other we’ve experimented with is a radiant heat using liquid glycol. This doesn’t freeze, but costs a lot to install on raised courts, since you have to have fittings for the tubes. It’s so close to the aluminum deck, [a downside is that] it sometimes flexes with the fittings, but once installed its really inexpensive to run.” Reilly Green Mountain has a testing plant in Orange, Connecticut, where they have set up a section of a court and leave it out all winter.

Speaking of inexpensive, installing propane heaters cost only $700 each, with an average of two heaters per court. However, the total bill for gas for the average four-court club reaches upward of $6,000 to $10,000.

Kempner is a proponent of hydronic radiant heat, which works well on helipads and hospital ramps. It would be embedded just below the court surface and would melt snow and ice, leaving a uniformly dry surface. He said, “The new technology in snow-melt solutions is revolutionary. It would also make

the courts more affordable. While it may cost the same to build, it would lessen the operating, in particular fuel, costs by half.”

Lighting

The technology is moving quickly, with tennis to thank for making big inroads in LED lights. Casiraghi stated, “Huts built in 2012 didn’t have LED; huts built in 2013 all have LED lights.” LED lights last much longer, about ten years, whereas metal halide, the previous standard, have to be changed every three to four years. Also, the LED uses less electricity, which cuts cost for users. As for the court lighting, array lighting may have its

use on our smaller courts, with directional lighting helping with those lost balls in the night sky.

Casigraghi said, “Right now, we have two clubs where we are testing two types of different wattage. Some of the questions are how bright the spot is and if you look at it, is it blinding? To test, we use computer analysis to see what should happen and compare that to what does happen on the court.”

Dodge has been working with stadium lighting for a few years, which offers much brighter night games. He said, “Although the stadium style fixtures have become the industry standard, we have been looking into and experimenting with LED for some time now. LED fixtures will offer greater energy savings and be maintenance free.”

Huts

Dodge stated, “Since the economy has loosened up, most projects are now two courts and a hut. There is a raised awareness, where clubs realize how the success of the sport benefits them.” Adding a well-outfitted but with new courts creates an instant mini club, which creates revenue. New huts have become multi-use facilities for clubs, who are willing to pay a premium for a well-designed building.

Wires

One of the industry frustrations is that the screen wire—with its particular gauge and tensile strength—is only available from Belgium. It used to be manufactured in Bridgeport, Connecticut, for prison camps, mostly. But after WWII, there wasn’t as much call for it. Dodge commented, “We are

begging someone to make our wire here.”

A player frustration is that there isn’t any uniformity regarding wire tension. David Meharg, of Putnam Tennis (newly partnered with Total Platform Tennis), is currently testing a tool that measures the consistency of wire tension. “Do you know how the builders test the screens? One of the crew members basically falls into the screens, putting all their weight into it and bounces off. One big sandwich at lunch might change how the wires are tightened! It’s not very scientific,” Meharg somewhat joked. “The screens have such a huge effect on the game. Some places the wires are dead, others loose, others just are right for you.”

Meharg invented a wire tension measuring device that reads the tension of the panels. When attached to the court, it gives a value to the tension of each screen panel. It quantifies a known amount, based on a scale of two criteria: deflection and balance. “The problem right now is, we don’t know what the best value should be,” Meharg explained. This will take player input and Meharg plans to arrange player testing after the winter season is over.

The extras you don’t really think about

Court Colors The surfaces are slightly more dynamic now, following in the footsteps of tennis courts. Gone are the brown and green that blended in to the natural surroundings. Courts are now blue and green or purple and green, with other options available. This has helped create contrast, particularly at night.

Door Closures Total Platform Tennis is a proponent of hydraulic closers. Dodge explained, “The old magnet ones stopped working well. We needed a magnet that worked well outside and couldn’t find one. The heat and cold doesn’t affect the new closers.”

What the game still needs

Meharg feels that the industry as a whole has to be more responsive with the delivery and installation of new courts. ‘We need to strike while the iron is hot. The faster we can build the courts, the faster people can get on them … there is a groundswell now and we need to take advantage! !” A collaboration between Putnam Tennis and Total Platform Tennis will hopefully increase their ability to manufacturer and deliver court systems and reduce the turn-around time on installations.

While new courts are being delivered in areas previously untouched, like New Mexico and Oregon, the mouse trap hasn’t changed since the 1970s.

Meharg, who has a technical background in the tennis industry, noted, “Most sports have constant improvement. The current court technology needs to be looked at and players have to be involved in the process. Surface technology has come a long way and the industry needs to comprehensively look at what the possibilities are and what is best for the players and the game.”

Dodge stated, “The growth of the sport is awesome – coast to coast, border to border.” Does innovation follow growth? If the builders and the innovators continue to invest in the game, there can only be a great future for the sport.

Source: Platform Tennis Magazine, Vol. 15, Issue 4 Feb/March 2014